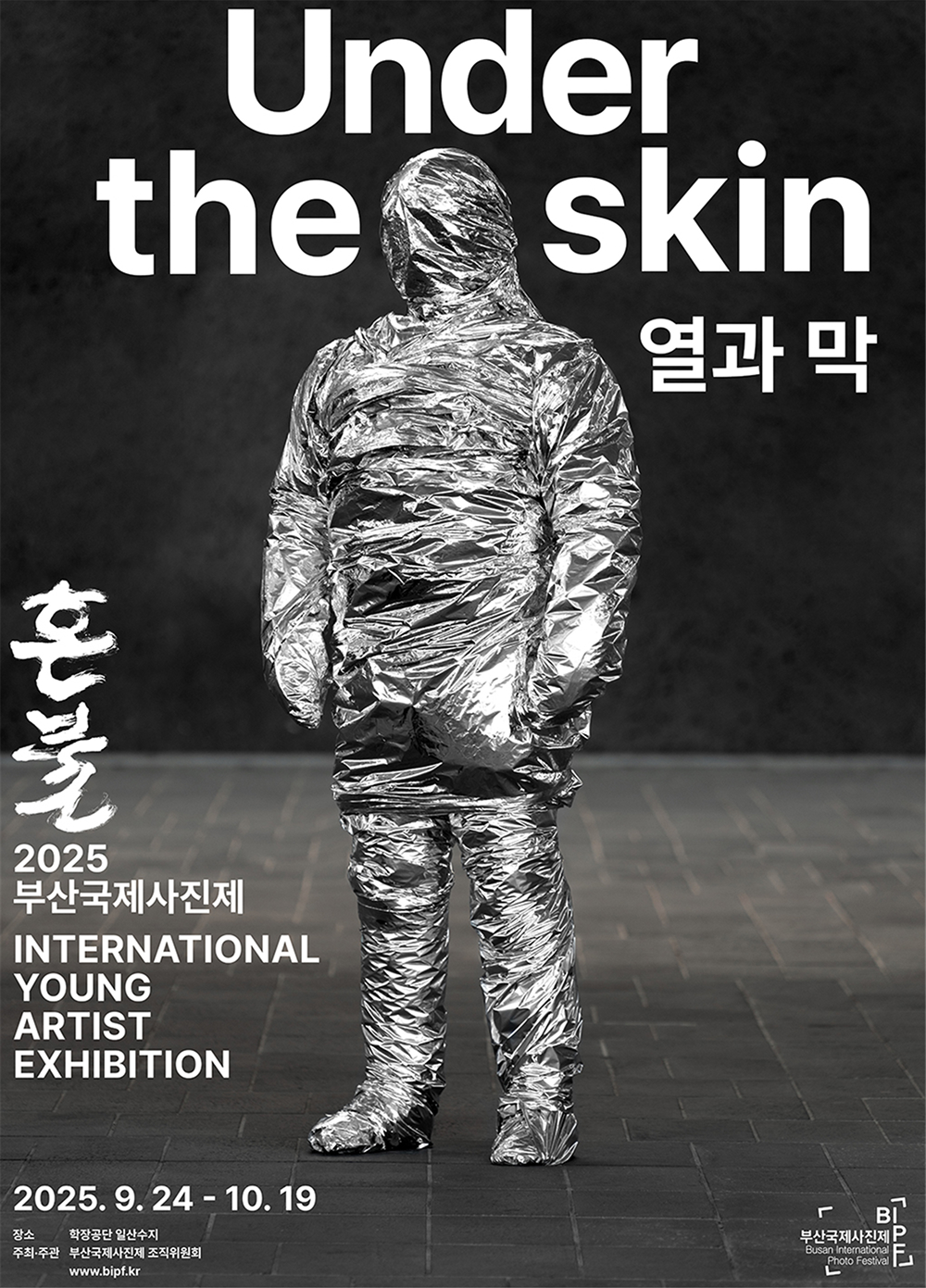

Under the skin ;

열과 막

A city is not just a densely populated settlement. It is a condensed network of

economic, social, cultural, and political relations, a vast organism that

constantly generates tension and rupture. Architecture, industrial structures,

and transport systems intertwine with layers of memories, relations, power, and

history. The city must therefore be understood as a field where pressure and

sensation intersect, where its surfaces absorb heat, leave traces, and form new

membranes in an ongoing cycle.

Busan exemplifies these urban conditions most vividly. Harbors and factories,

residential quarters and commercial districts collide; development and decline

unfold simultaneously, shaping the texture of its urban space. Traces of

industrialization, fractures of redevelopment, memories of wartime refugees,

and influences of international exchange all construct the layered fabric of the

city. This exhibition, Under the Skin: Heat and Skin, frames these conditions

through two concepts: heat, which refers to structural tension and social

pressure, and skin, which denotes the boundary through which individuals’

sense and respond to the heat. Photography operates as a medium that

mediates between these two—another skin that records and transmits.

The exhibition venue, Ilsan Suji, also clearly reveals this notion. Once a plastic

recycling and dyeing factory, the site retains its rough walls, high ceilings, and

traces of industrialization. Reborn as a space for artistic experimentation, it

functions as a membrane which bears a residue of the past pressure and where

new sensibilities emerge, directly resonating with the theme of this exhibition.

Participating artists explore relations between city, society, and individual

people in their own unique ways. Kwak Dong Kyung traces desires that were

disregarded during the historical and industrial transition while Kwon Ha Hyung

documents changes in his redeveloped hometown with a personal affection.

Kim Yoo Na visualizes invisible psychological distances between people, and

Kim Hyo Yeon examines how historical events intersect with family narratives

and affect both individuals and communities. Shin JungSik records his father

living with Alzheimer’s disease, focusing on the fragmentation of memory, while

Alex Sim bring into focus everyday detail and warmth through bathhouses as a

communal space. Yoon Ami draws attention to pain and vulnerability within

relationships, expanding personal memory into collective history. Lee Jae Kyun

captures unseen structures and sentiments, revealing fragility of a society that

heavily depends on technology, and Choi Won Kyo experiments with

photographs as a means of documentation that has the potential for

manipulation, exploring the tension between immateriality of the digital

technology and physicality of form.

International participants also reinterpret memories and traces in their own

contexts. HsuanLang Lin documents Taiwanese streetscapes and

atmospheres, exploring the tension between alienation and belonging. Yu Hsiu

Huang investigates the psychology of those who experience social

misrecognition through spaces and portraits. Jing Hong Jhang reinterprets

relations between environment and culture, visualizing physical and

psychological dimensions of religious rituals and the community. Julia Lübbecke

builds anarchive that uncovers the history of institutional care, violence, and

resistance. Oscar Lebeck documents landscapes of ruins, asking whether

memory can be fixed in space. Philip Tsetinis combines fictional scenarios

about the future with autobiographical elements, balancing documentary

aesthetics and surreal construction. Takahiro Mizushima transforms

photography into a resonant site through installation, linking the city, people,

and acts of recollection.

Works of Choi Won Kyo, who experiments with the physical expansion of

photography, and Lee Jae Kyun, who utilizes the medium’s immediacy to create

a metaphor, highlight their distinctively different approaches. Meanwhile, works

of other artists commonly focus on personal memories and historical remains

excluded from official records. Kwon Ha Hyung’s records of old city centers,

Kwak Dong Kyung’s empty spaces in the alleys of fantasy, Shin Jung Sik’s

family memories, Takahiro Mizushima’s routes of recollection, Kim Hyo Yeon’s

intersections of the personal and historical events, Yoon Ami’s statement

through the body, Oscar Lebeck’s landscapes of ruins, and Julia Lübbecke’s

archival experiments all link fragments of the past to the present. Kim You Na’s

depiction of marginalized individuals, Alex Sim’s records of disappearing

bathhouses, Yu Hsiu Huang’s Hoarders series that show rooms isolated from

the outside, HsuanLang Lin’s observation of his hometown as an outsider, and

Jing Hong Jhang’s documentation of collective rituals all align with oral-

historical methodologies. These works recall what Walter Benjamin described

as the “flash-like moment of history,” summoning the past to the present. Philip

Tsetinis’s images, in particular, show gatherings of a few depressed individuals,

but they do not revisit moments in the past; rather, they appear to reveal a

scene from the future that has not come yet.

At the junction where personal voices and historical fragments meet,

photography functions as a medium that records this intersection. A city is a

place where private and public memories accumulate and transform into record

and history. Within this space as a vast organism, individuals may appear small

components, but each of them has a unique value at the same time.

Photography records these layers, allowing viewers to simultaneously perceive

personal anguish, traces of industrialization, and social discourse. Under the

Skin: Heat and Skin is where modern cities and people living in them are

observed through the lens within the historical context.

Curator Son Changan, Lee Jeongeun